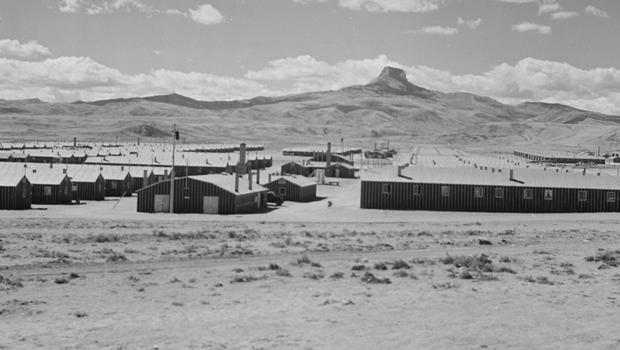

As the story goes, Heart Mountain in Wyoming got its name from the Crow Indians, who thought it looked like the heart of a Buffalo. Rising nearly 8,000 feet, it’s often shrouded in clouds. But far below, the dark clouds of history still linger.

For it is here where the ghosts from one of America’s most shameful chapters still roam.

“The whole time was one of tension, chaos, not knowing what was going to happen next,” said Norman Mineta.

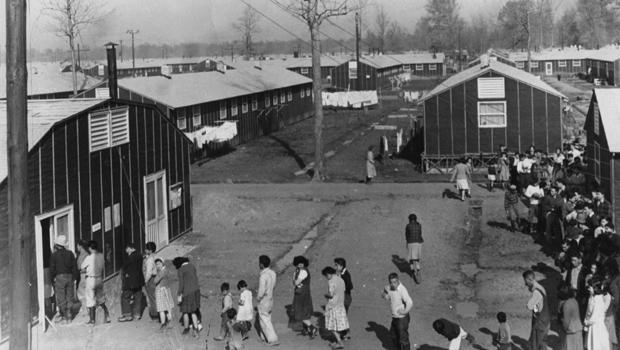

It was shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor that an executive order from President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered anyone of Japanese descent living along the West Coast be relocated. As many as 120,000 people – most U.S. citizens – were rounded up, loaded onto trains, and sent to places penned behind barbed wire, their loyalty and their patriotism questioned.

“I remember in grammar school in San Jose, you know, we would all want to fight to be the one to carry the flag when we did the Pledge of Allegiance every morning,” said Mineta. “So, now here we are behind barbed wire, thought of as not citizens.”

The internment camp erected in the shadow of Heart Mountain in Wyoming. CBS NEWS

Like so many others, Mineta, born and raised in San Jose, Calif., to Japanese parents, was uprooted from his home, having no idea where his family was headed, or for how long.

“On that day that we left, I was wearing my Cub Scout uniform. Baseball, baseball glove, baseball bat. And as I got on the train, the MPs confiscated my bat.”

“They took your bat?” asked CBS correspondent Lee Cowan.

“And I went running to my father crying about the MPs.”

Heart Mountain was one of 10 camps the government hastily constructed. The Minetas arrived on a windy day in September 1942, moving their few belongings into their tar paper barrack. “There was only one light in that 20-by-25-foot room. Held my mother, my dad, two sisters, my brother and me,” he said.

“And out of all the people who were brought here, what percentage of them were citizens?”

“Two-thirds, close to 70 percent.”

At its peak, the camp held some 14,000 internees. That technically made it Wyoming’s third-largest city at the time – even bigger than the nearby town of Cody.

At its peak, the population of the Heart Mountain internment camp was about 14,000. CBS NEWS

A young Alan Simpson lived just down the road. “The signs would go up: ‘No Japs allowed. You sons of bitches killed my son at Iwo Jima.'”

Cowan asked, “Were you worried about that as a kid?”

“Well, you would, because there was barbed wire all around the dammed thing, and guard towers and guys with guns and searchlights all aimed inside,” Simpson replied. “So, wouldn’t you as a 12-year-old kid think there was something in there? I think you would.”

The camp did operate like a small city. There were schools and farms and churches, even elections. But there was also boredom.

To keep internees occupied, the agency in charge, the War Relocation Authority, allowed activities like ice skating, baseball, and (much to Mineta’s surprise) scouting.

But his was a lonely troop.

“Our Scout leaders would write to the Scouts in all the towns surrounding Heart Mountain: ‘Come on in for our jamboree,'” Mineta said. “And they’d write back and say, ‘No, no, those are prisoners of war, so we’re not going in there.’ So they’d write back and say, ‘No, no, no, these are Boy Scouts of America. They wear the same uniform you do; they read the same manuals you do.’

“But none of them came in.”

Except, that is, for one: Alan Simpson’s Boy Scout troop.

His forward-thinking scoutmaster, Glenn Livingston, thought a visit to the camp embodied what the Scouts stood for. And soon, Simpson found himself tying knots across from a Japanese-American boy who would become his life-long friend.

Boy Scouts Alan Simpson and Norman Mineta. CBS NEWS

“He always called me pesky, a pesky little rascal,” Mineta said.

“He was a spirited lad,” said Simpson.

Which meant what? “It meant he was as ornery as I was. And we could figure out ways to screw up anything we could get our hands on.”

They shared a tent, and that’s where their trouble-making started, playing a prank on a fellow Scout from Simpson’s troop.

“There was kind of a bully and it was raining to beat hell and we kinda channeled the water down into this guy’s tent,” Simpson said.

“On purpose?”

“Oh yes!”

Mineta said, “We built a beautiful moat, and the tent came down.”

“Norm says that I cackled as that happened.”

Did he? “Well, I’ll tell you there were a lot of hee hee hees, a lot of ha ha has, lot of ho ho hos!” Mineta affirmed.

As their time together unfolded, Mineta remembers seeing a change coming over his new friend: “He realized these are American citizens, and now they’re behind barbed wire.”

“They were American citizens. They were American boys,” said Simpson.

“Even as a 12-year-old he thought that was just totally unjust,” Mineta added.

Neither forgot their shared experience that day. They carried it with them through the decades that followed, through marriages and family, but all of it apart from one another.

They never saw each other until Simpson read that Mineta had become the mayor of San Jose. “So I wrote him a note. And he wrote back saying, ‘Oh yeah, maybe someday we’ll see each other or something, you know?'”

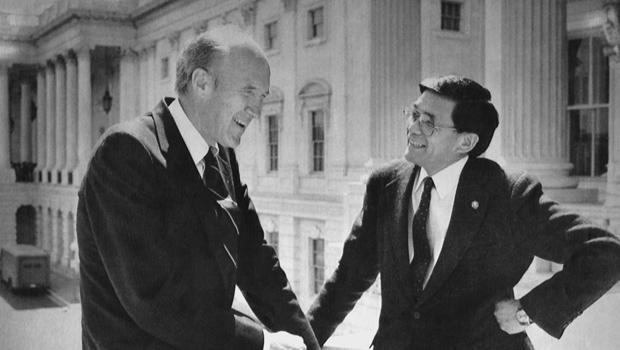

Simpson noticed because he, too, had gotten into politics. He grew up to become Wyoming’s outspoken senator, a seat he held for 18 years, as a lifelong Republican.

Mineta, who became a Democrat, went from that mayor’s seat to Congressman, and then all the way to Cabinet Secretary, under not one but two U.S. Presidents.

So that is where the two former Boy Scouts reunited, under the Capitol Dome, some 35 years after they first met. “And there we were, and we started right over just like that,” Simpson said.

“And our friendship went back as if we were still sitting in that pup tent!” Mineta said.

Republican Senator Alan Simpson of Wyoming, and Democratic Congressman Norman Mineta of California.

CBS NEWS

In 1988 Simpson and Mineta joined forces to help pass the Civil Liberties Act, signed by President Ronald Reagan, which for the very first time formally apologized to Japanese-Americans and granted reparations to those who had been imprisoned.

Cowan asked, “Are you surprised that he’s not bitter about what happened to him?”

“That’s the real one,” Simpson replied. “He’s a Mandela-type person. Bitterness never came over him.”

They didn’t always agree on everything, but party – like that barbed wire – rarely came between them. And even when it did, they say it wasn’t as pointed, or as personal, as the debates that dominate politics today.

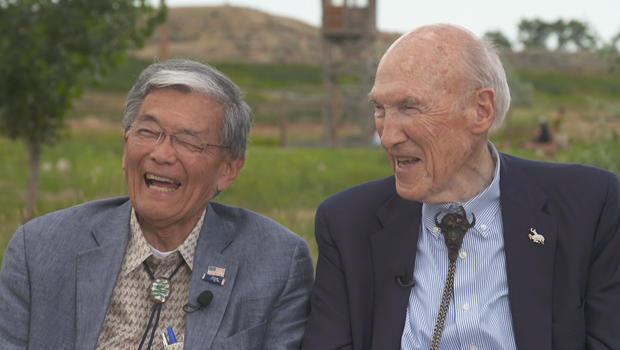

Norman Mineta, a former Democratic Congressman and Cabinet member in both the Clinton and Bush administrations, and Alan Simpson, a former Republican Senator from Wyoming, talk about a friendship forged when both were Boy Scouts, on opposite sides of a barbed wire fence, during World War II.

Simpson said, “The word ‘politics’ is interesting because it comes from the Greek, you know that? Poly, meaning many, and tics, meaning blood-sucking insects.”

Mineta said, “We’d have fights in the sub-committee, the full committee, and yet we’d slap each other on the back and say, ‘Come on, let’s go have dinner, let’s go have a drink.’ And they don’t do that [today]. They just don’t have that kind of personal relationship.”

Both Mineta and Simpson are happily retired now, and every year return to Heart Mountain to help remind generations that came after theirs just how fragile freedom can be.

Every year the crowd gets bigger, which says something about the growing interest in keeping what happened here from ever happening again.

A watchtower at the site of the Heart Mountain Relocation Camp.

But in the midst of this somber memorial, this unlikely duo brings some much-needed laughter, too.

Simpson said, “We don’t talk of Scouts and tying knots. We have organ recitals. How’s your heart? Liver? These are called organ recitals!”

Mineta said, “I really admire him, respect him, and love him. He’s just a wonderful, wonderful individual.”

“We see each other and we just begin to laugh. There’s no way to describe it. It’s a love affair, I guess that’s what you say. We just have fun together.”

Yes, there is a dark history here, but the human spirit is brighter. A friendship that reaches back decades has managed to shine the light of hope for generations.